India 2036: Hosting Olympics is a whole new ball game – on the field and off it

Last week, during the opening ceremony of the International Olympic Committee session in Mumbai, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said India was “eager to host” the 2036 Olympics. He spoke at length about India’s capabilities in organising big events, and specifically mentioned the recent G-20 series of meeting, held in 60 cities across the country during the past year.

There’s no denying India’s logistical capabilities, in the sporting sphere as well – witness the smooth staging of the Indian Premier League every year, and even the ability to switch entire countries at the last minute, as it did in 2009 when the tournament was played in

South Africa.

But though the G20, the IPL, even the current cricket World Cup are large and complex operations, the Olympics is a beast on a whole different scale – from security to transportation, people to infrastructure, and especially scrutiny, accountability and synchronising with a large and powerful organisation (the IOC).

Here’s a look at the some of the challenges in hosting the Olympic Games:

THE TANGIBLES

The scale

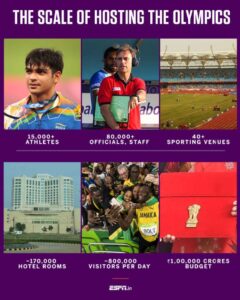

The sheer scale of the Olympics is unimaginably bigger than any sporting event on the planet. The Tokyo Olympics saw more than 11,000 athletes compete in 42 venues across Japan. They also hosted around 80,000 overseas officials, support staff and journalists (expect that number to increase with additional sports). And we haven’t even gotten to the fans, who were absent in COVID-19 hit Japan. And then the Paralympics, which follow immediately: a further 4403 athletes, plus officials and journalists.

While Tokyo’s hotel occupancy (which was still increased by 6.4% before the pandemic hit) and public transport weren’t tested to the hilt because of the pandemic-enforced absences, they have been elsewhere. Rio De Janeiro, for instance, added 31,960 rooms (a 16.8% increase on existing volume) ahead of the 2016 Games… and this was after an increase had already happened for the 2014 FIFA World Cup. This was then further augmented by AirBnB facilities.

Paris, the hosts for the next Olympics, has one of largest accommodation volumes in the world (~160,000 hotel rooms already available), but they also expect to add more rooms (a minimum of 5000). Meanwhile, the city expects to carry between 600,000 to 800,000 Olympic visitors per day on their public transport system. “It’s like being in permanent rush hour,” is how the French transport minister put it. A new metro line has opened from the second airport in the city (Orly) to an Olympic hub; and an express train service is set to start from the primary airport (Charles de Gaulle). They expect to have even more trains and shuttle buses running.

View from the mostly abandoned Olympic Aquatics stadium in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil the nine months after the 2016 Games. Buda Mendes/Getty Images

India won’t be awed by numbers but there needs to be a huge amount of building to handle such a targeted surge. To provide context, New Delhi’s hotel capacity is slightly under 15,000 rooms; add Noida and Gurugram and it’s still only about 23,000 rooms.

Ahmedabad currently has 4,350 rooms and it cracked under the weight of hosting one India vs Pakistan cricket match during the ongoing World Cup. India vs Pakistan in cricket could just be one of many, many high-profile contests at the Games.

This can, of course, be solved by having more facilities spring up in the host city but that leads to a major question (one that Rio continues to face): who will use them after the Games is done?

Infrastructure

The answer to that depends a lot on where India wants to host the Games. There are existing sporting facilities in big cities that, with a lot of refurbishing, could be made fit to purpose (and there’s time enough to do all that). The Olympics, though, is a vast sporting universe unto itself. It includes sports that require super-specialised infrastructure and have very strict guidelines to adhere to.

This generally works out to the host needing at least 40 different sporting venues (each with their own requirement – like open water, or a hard floor gymnasium, or specific ramps and pipes). And building these from scratch is not just incredibly expensive but needs to meet a very important host selection criteria: any new stadiums built would need long-term legacy justification and fit the needs of the local population.

You can utilize structures already present elsewhere in the country – like in the 2024 Games, Nice will host group stage rugby and Marseille group stage football – but those in India would need major refurbishment. For example, the only track cycling (12 medal events) velodrome in India is a rundown, little-used facility in New Delhi. Hosting a Games, say in Ahmedabad, with the track cycling in New Delhi could be an option, but logistically challenging.

Besides these special facilities you would need state-of-the-art Games Village accommodation, security facilities and other amenities: and they all must work like clockwork.

And no, all this doesn’t pay for itself.

The financial investment

The Tokyo Olympics cost US$13 billion (> Rs 1 lakh crore) to host – this was 130% higher than the estimates released when Tokyo won the bid in 2013. 62% of this cost was covered either by the Tokyo government or the Japanese central government.

These costs were, of course, spiked by the COVID-19 pandemic but the fact remains that it is a major financial investment. According to the LA Times, Paris 2024’s cost has climbed from EUR 6.8 billion (~ Rs 60k crore) to EUR 8.5 billion (~ Rs 76k crore), with further rises expected. Los Angeles 2028’s cost is estimated now at US$6.9 billion (~60k crore) excluding security costs and public transportation.

A faded Beijing 2008 sign in the beach volleyball stadium built for the Beijing Olympic Games. GREG BAKER/AFP via Getty Images

It also affects general tourism if a city that’s already a popular destination is chosen. For instance, net tourism fell by 5% in London (in 2012) and by 20% in Beijing (2008).

There is a reason many in-city voting referendums forced cities like Rome, Hamburg, Boston and Bern to pull out of the running for hosting an Olympics at various points. Ticket sales can only make up for so much, and corporate sponsors have always only covered a percentage of the costs involved. Hosting a Games is a loss-making enterprise on a purely financial barometer. Ask Greece.

Legacy

Once again, say the host city is Ahmedabad. If the city’s hotel and accommodation infrastructure is increased by 5x (a very modest estimate), what happens to all of it after the rush of the Games? Would the city of Ahmedabad be able to provide sustainable volumes of occupancy? For instance, the additional rooms created in Rio have been a major problem for the hotel industry in the city.

That’s just the support infrastructure. What happens to the sporting ones? In Beijing, a number of purpose-built smaller stadia for the 2008 Games lie abandoned, while the showpiece Beijing National Stadium (Bird’s Nest) is now a tourist attraction that hosts a range of events from exhibitions and concerts to the occasional pre-season friendly football match. In Brazil, even football stadiums built for the 2014 World Cup have fallen into disuse and disrepair.

While the focus of the IOC has shifted to venues that have sustainable infrastructure, not everything will be utilized at capacity. One solution could be to designate the host city as the nation’s sports-capital going forward, for all major sporting events. But that carries with it one big risk (empty stands if the city’s sporting culture isn’t strong enough/the fact that not all tournaments will be high-profile) and one big downside (keeping the best sports away from everyone else in this vast nation).

Bums on seats

This is a mix of the tangible and the intangible. Just how many bums will be on the seats at these stadia? The Indian Women’s League football tournament struggled to get double-digit attendances across a month in Ahmedabad, and even the cricket World Cup is visibly struggling to get people in for non-India matches across the country.

The sight of empty stands on the opening day in Ahmedabad was painful – here were two of the best exponents of the sport India loves more than any other battling it out at the biggest stage, and yet the Narendra Modi stadium was at around 35% capacity. The game between Afghanistan and Bangladesh drew a crowd of 9,195 (two of India’s neighbours!), the game between England and Bangladesh 12,478: both were held in Dharamshala, where the stadium capacity is 23,000.

This comes down directly to a sporting culture that, although it has changed considerably over the past decade-and-a-half, is still far too much a TV-centric fan base. The ICC World Cup has shown that clearly there’s a long way to go. At every Olympics, while there will always be foreign spectators flying in, domestic attendances make up the bulk of the crowd. Will that happen here?

India’s sporting quotient

Olympic success is not an essential criterion for a bid, but it would be embarrassing, to say the least, for the host nation to be out of the running in most events early on. In Tokyo 2020, India won seven medals. In its history, India have won 35 Olympic medals — that’s as much as Michael Phelps and Usain Bolt combined.

When Japan put in the bid for Tokyo 2020, they were coming off an Olympics where they had won 38 medals. Rio 2016 came on the back of 17 won by Brazil in Beijing 2008.

Post the 1970s, the lowest any winning nation had at the time of bidding is 8, which Greece had won in 1996 (4 of those gold). But they ended the 2000 Sydney games with 13 medals (4 gold, again) and their home 2004 Games with 16 medals (6 gold). This shows that a targeted improvement is possible; but Greece also warns off a sharp fall off – in 2008 they won three medals (0 gold), in 2012 two (0 G), before improving to six in 2016 (3 gold).

There is time for improvement to be charted out, but there is also a lot of ground to make up.

Dress rehearsals

The basic infrastructure and other capabilities will have to be tested at the venue sometime before the Olympics are held. It could be the National Games, held in Gujarat last year; but the one before that was seven years previously in Kerala. This highlights the sporadic nature of the conduct of the national games; an aspect that needs to be improved considerably.

Rio had the FIFA World Cup in 2014 (considerably larger scale than the cricket iteration), and the city saw Argentina descend upon it for the final. Rio and Paris also have a rich sporting culture, with attendances at stadiums for sporting events consistently high and tournaments held year-round across different sports.

Modi, in his speech to the IOC, mentioned that India would be “eager” to host the 2030 Youth Olympics, and that might a good dress rehearsal. It would be lower-cost than staging either a CWG or an Asiad before the Olympics.

THE INTANGIBLES

Putting people first

The most important thing to remember at such a large, multi-national event is that people matter. Athletes matter. Support staff matter. Fans matter. Journalists matter. Officials and backroom workers matter. It may sound strange to have to mention this but our sporting culture tends to take all these people for granted. That’s why stadiums are filthy, hard to access, without basic facilities, all of which make a sporting experience in India a nightmare for fans – and not much better for travelling journalists. And the ticketing process will have to start many months before the Games begin.

At the Olympics, every nation on the planet will be present — there are more National Olympic Committees recognised by the IOC (206) than there are nations in the United Nations (193) — and an Olympic accreditation card is akin to a diplomatic passport, giving instant access to the host nation. In this scenario, there is no room for delays or other issues with visas for fans or journalists. Everyone has to be treated equally.

There’s another factor to keep in mind during both the Olympics and the Paralympics: making all infrastructure special needs-friendly. It’s fair to say that very little of our public space in India today meets those requirements; that will have to be up to scratch.

Better sports governance

At its session in Mumbai, the IOC raised the issue of the Indian Olympic Association not having a CEO; by its norms, the current acting-CEO, Kalyan Chaubey, cannot continue in that position while also holding president-ship of a sporting federation (the AIFF). That is just the tip of the sporting governance iceberg – things get far messier down the line, where state bodies and district bodies do the bulk of the work.

Our national federations have often been an embarrassment – look at the Wrestling Federation of India, for instance – and the country cannot afford to be shown up on the biggest stage of them all. What it needs, from day 1, is a professional approach – something we’ve rarely seen when it comes to the conduct of sporting tournaments. (With one exception, the consistently professionally-run IPL.)

There remain vast issues that need to be addressed: from minute aspects like drug testing to the actual conduct of tournaments (at the National Para Games a few years back, one event was conducted under car lights). There’s all this low-profile, non-glamorous stuff we overlook and correcting this will need a wilful effort from everyone in the sporting pyramid.

Scrutiny and accountability

Any major bid of this sort comes with the sort of expenditure that needs great scrutiny and continuous monitoring – and that kind of accountability must be automatic, considering the financial burden to the taxpayer.

What also needs scrutiny, though, is how the sporting system is set up. A successful bid will do one thing for athletes, guaranteed – funnel more money and better support to elite athletes (you can’t host a Games and finish 48th in the table), but what of the rest? What of sustainable sporting systems that allow sportsperson to compete at their best level across the nation? Putting in place the kind of accountability that will ensure this would be the greatest legacy hosting a Games would have.

It’s important to note that, in terms of scrutiny and accountability, hosting the Olympics is different to hosting the G-20 or even the ICC World Cup. The IOC has clear rules on sustainability, expenditure, standards, protocols and it will demand and expect levels of scrutiny not just of Indian sports officials but, ultimately, the government of the day.

If India’s sporting system can come out of all this unscathed, that could be a positive long-term impact of hosting the Olympics.

ESPN